It’s been 10 years since Fujifilm first offered the Samba printhead to other OEMs and it’s remained a market leader throughout that time so it’s worth taking a deeper dive into the technologies behind this head.

Fujifilm put a lot of effort into developing not just the Samba printhead but also the MEMs technology that underpins it. I’ve already covered this in an earlier story, along with the recent upgrades that Fujifilm has made to the Dimatix facility in California. Bailey Smith, vice president of business development for Fujifilm Dimatix, noted: “There have been lots of improvements but the head itself has not got any faster in the last 10 years.” However he goes on to point out that the uniformity has got better because the PZT is laid down better, as we saw in the first part of this story.

The Samba was primarily designed for single pass inkjet printing. In the past, Fujifilm has also produced a version for scanning applications, the Samba GMA, but this has been discontinued. There are currently two variants on the Samba printhead. Both share the same basic design with 2048 nozzles with a 43mm print width. They both have a firing frequency of over 100 kHz, both operate at up to 60ºC and both can produce 1200 dpi resolution. The Samba will work with a wide variety of different ink types, including water-based inks. Terry O’Keefe, senior product manager for Fujifilm Dimatix, notes: “There’s no electrical communicating in the ink path so we don’t care if it’s conductive or non-conductive.”

However, there are some differences worth noting. The G3L has a 2.4pl native drop and can produce drops up to 10pl, with a maximum productivity of 360ng-kHz, which translates to printing at around 120mpm. It runs UV inks as well as aqueous, latex and solvents and has a viscosity range of 4-8 cPs. It’s mainly targeted at higher image quality applications such as labels and flexible packaging. It’s worth noting that the two fastest inkjet label presses, the Durst Tau and Bobst Digital Master, both use the Samba and both run at 100mpm at 1200 dpi.

O’Keefe says: “We see the 2.4pl output as perfect for the 1200 dpi output. There are some applications that want to see smaller but for the bulk of the printing market 2.4pl is fine. But you have to be able to reach the optical density and reach full coverage. So we need greyscale for a larger drop and we have to be able to do that at speed. I think the highest image quality will average at about 100mpm.”

Then there’s the G5L, which has a 3.5pl native drop and a large maximum drop size of 13pl. It can produce 450 ng-kHz, which leads to a print speed of up to 150mpm. It will run aqueous, latex and solvent inks, from 5-9 cPs viscosity, but is not targeting UV inks. This variant is mainly aimed at applications such as textiles and corrugated packaging. In addition, some devices, such as the BHS inkjet corrugating unit, which was developed by Inca Digital, now part of Agfa, uses a double row of print bars to achieve speeds of up to 300mpm.

From left: Dave Pulizzi, VP of operations; Darren Imai, VP of MEMs R&D; Terry O’Keefe, senior product manager; and Bailey Smith, VP business development.

Leaving aside the basic specifications, there are a number of other features that have contributed to the enduring success of the Samba design. Top of this list is the MEMs manufacturing approach. O’Keefe explains: “We build up structures through the head to ensure we have a uniform flow.” He adds: “You have to have the nozzles aligned into the right place and that’s one of the characteristics of MEMs. Especially in packaging where you run at higher stand-off. You don’t want to lose image quality at longer throw distances. So the nozzles have been optimised for higher stand-off.”

Another important factor is the use of ink recirculation right through to the nozzle plate. O’Keefe says that there will always be nozzles that don’t fire as frequently and so it’s crucial to have the ink recirculate all the time. He explains: “We don’t want the last nozzles to get less or the first one to get a faster flow. We have a metal manifold that pushes the ink down to an interposer. Each bank of nozzles feeds off one set and the recirculation flows from one to the other bank. The ink goes from the feeder to the actuator and then back to an in-feeder but then out to the return, not back to the nozzle. There are bypasses through the head to allow for balance so that there’s no cross talk between the nozzles.”

It’s a complex system, but as he notes: “The MEMs design gives you the space to have all the fluid piping and the electronics. You can do similar with other heads but as we get faster you need this kind of complexity.”

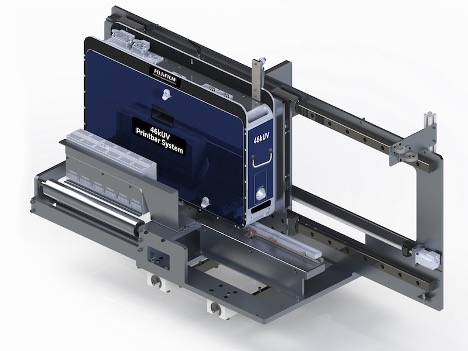

Fujifilm’s 46kUV printbar is based around Samba heads and targeted at the labels and packaging markets.

In an ideal world, all the ink that is ejected from each nozzle will go on to land on the substrate. In reality, tiny amounts of ink break away from the main body of their ink drop, usually as the tail of that drop stretches away from the nozzle. This creates an ink mist, which is then blown back over the printheads by the turbulence that comes from the movement of either the substrate in a single pass system or the head carriage in a scanning system.

This ink will collect on the nozzle plate and has to be cleaned away before it can clog up the nozzles. However, the cleaning leads to the risk of damage through wear and tear from continually wiping the nozzle plate. Consequently, most printheads have some kind of coating to protect them from chemicals within the ink and to aid with this cleaning.

Fujifilm’s solution is its RediJet Coating, or RJC, and customers now have an option between the original coating and a new version, depending on the ink they are using. O’Keefe explains: “We have to be able to cope with all the inks that are coming out. When we started we had one coating but there are new inks and they might be more aggressive and have different characteristics so we developed other coatings to match those new ink sets.”

He adds: “All the bulk of these inks work fine with Gen 1 RJC. But as we have seen more challenging inks, we have had some difficulties. It could be a chemical attack or mechanical from wiping the inks. So we have the new Gen 2. If the customer’s inks work fine with Gen 1 we use that. But if we find their inks are more challenging then Gen 2 is the option.”

The Parallelogram shape

Another defining element of the Samba is its parallelogram shape. Most printheads are rectangular blocks with rows of nozzles across their width. The most common way to create a page-wide array is to offset every other head on a second row behind the first so that the rows of nozzles can overlap. This creates added complexity in stitching the heads together and necessarily takes up a lot of space, particularly if there are a lot of colours, each with its own printbar.

Every Samba printhead has an EPROM module with information on its performance.

The Samba’s parallelogram shape overcomes this, allowing each head to be slotted together in a single row, with the rows overlapping so that they’re easily stitched together. O’Keefe explains: “It’s not 1200 dpi all the way to the end but across the bar. That’s the key behind the parallelogram approach which is why it has that unusual shape.”

The design includes a clamp to hold each head in while also making it easy to swap one head out for another. There is a gap between each head in order to slide out whichever one needs to be replaced. There are little screws on the clamp that allows for precise positioning. O’Keefe notes: “Cross process is the most critical issue which you can deal with through those screws. They are pretty close to begin with.” Indeed, there’s one whole area in Dimatix’ Santa Clara facility just to put the dovetail bracket on the Samba and to ensure the heads can be aligned properly.

Implementation

Despite the claims of some OEM press vendors over the years, Fujifilm supplies the same basic heads to everyone. There are some options, also available to all customers. Smith explains: “For certain applications we do have some variance. And customers might want to have some specific changes like longer tubing. And we do have different coatings, but for different application classes not for different customers.” Equally, some customers, such as Bobst, choose not to take Fujifilm’s mounting bracket, and develop their own method of aligning each head.

The thing that really sets apart each vendor’s implementation of the Samba, apart from their ink, is the waveform they use to drive the head. Depending on the waveform, the Samba is capable of delivering at least three pulses at 80kHz. O’Keefe says that this is more than enough for most customers, adding: “The typical way that most people use the head is with three drop sizes. One for fine detail, two for coverage and a third for compensation.”

Within this there is considerable freedom for customers to use the waveform to determine the drop sizes they want for their applications. Moreover the different drop sizes can be produced at the point they leave the nozzle. This differs from some other greyscale approaches that produce the same size drop, or drops with very little variation, and then rely on the drops to catch up with each other in flight or at the point where they land on the media in order to produce larger drops.

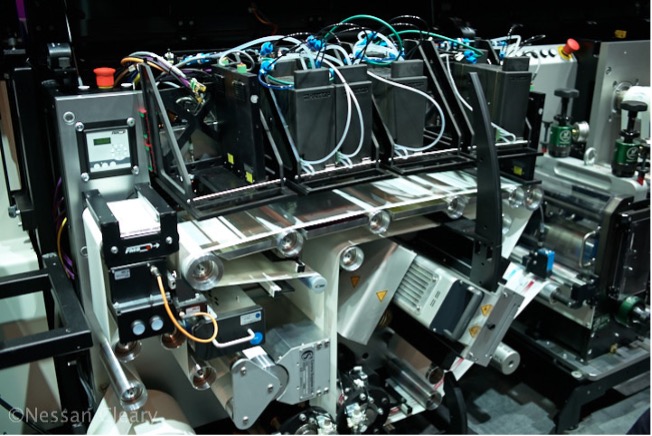

The Mouvent printhead clusters that Bobst uses consist of four Samba heads within a 3D-printed housing.

Some OEMs have expressed some frustrations to me over the years with the Samba, such as difficulties in recovering from a problem if air gets into the system as the head has to be primed with the air pumped out first before the head can get back to work. Others have mentioned issues around tuning the head to the ink and optimising the waveforms.

O’Keefe acknowledges that the OEM customers will have to do a lot of work to get the best out of the printheads, particularly in terms of building waveforms and testing their imaging systems, adding: “We can do a lot to help with this.” He continues: “Some people want to do a lot of testing. If you are buying our product we will help you and that’s an important enabling tool to move testing at customers along.”

It’s also worth noting that the Samba is mainly used by OEMs operating at the top end of their game in single pass inkjet printing, such as Agfa, Durst and Bobst, all of whom have the capability to squeeze the best performance out of this head. More importantly, there aren’t many alternatives that offer the same level of sophistication combined with both high speed and high resolution.

Smith says that Fujifilm is actively engaged with its customers and their requirements, noting: “Nobody is asking for more than 1200 x 1200 dpi resolution. But they do want to see more productive speed with more laydown and image quality, but running faster.”

Future growth

Although it’s been 10 years since Fujifilm started offering the Samba printhead to other OEMs, the head itself predates this as it was originally developed for Fujifilm’s Jetpress 720 single pass inkjet press, which was designed for commercial printing. This was first shown as a prototype at Drupa 2008 before being officially announced at the Ipex 2010 show. Since then Fujifilm has continued to refine the press, up to the latest Jetpress 750S model.

In addition, Fujifilm’s Integrated Inkjet Solutions division uses the Samba for its range of printbars, including the recently announced 46kUV, and the four colour 12K printbar.

Fujifilm showed the Jetpress 720 as a prototype as Drupa 2008.

The Samba has also been used in a number of label presses, such as the Durst Tau and Bobst Master Expert, as well as several inkjet packaging presses, including the Agfa SpeedSet 1060 and the VariJet 106 from the Koenig and Bauer Durst joint venture. Smith says that the textile and packaging markets are witnessing a conversion from analogue to digital manufacturing, noting: “We have seen increased demand primarily in labels, textile and commercial print coming out of Covid.”

He continues: “There are applications that do not need the same speed or the resolution or the head life. These aren’t really the markets that our products are well suited to. We want the printheads to last three to four years. We are focussing on these very high demanding market spaces.”

Smith concludes: “There’s a lot of opportunity for the top performing and most durable products. We won’t get all of that but we feel there’s enough there for us to continue to expand. We have had ten years of perfecting this technology and we feel this technology can advance us pretty well in the future.”

You can find the first part of this story, on the Fujifilm Dimatix MEMs facility here. Fujifilm lists details of its Dimatix industrial printheads here.