The Recirculation Revolution: How the History of Inkjet Technology Changed Interior Design

Print was done by a combination of flat-screen printing or rotary blanket printer, such as the System Rotocolor machine. Both techniques involved contact to the un-fired (green) tile, thus requiring a certain thickness to give the required strength to withstand the contact force. The printing also involved set-up related to patterning of the screens, or the blankets, and the changeover of these meant stopping the lines.

Shorter run lengths of seasonal designs were not economical and so the cash held in inventories was huge. Like it has in many other industrial segments we have discussed, digitizing the manufacturing of ceramics allowed for much more freedom to realize the dreams of designers, this time to create modern living spaces such as shown in our lead image above. As a result, the value proposition for buying a printer was undeniable and so the adoption rate was unprecedented, making ceramic tile production the inkjet case study.

The Defining Single-Pass Industrial Business Case

Digital printing addresses many of these challenges, but especially the number of tiles of a certain design that are needed to be kept in stock.

Ceramics has become the go-to inkjet proof-point for demonstrating the benefits of minimizing inventory where design versions exist, and can be re-printed when needed. To enable the digital printers to match the existing production style, single-pass printing was necessary: the tiles would pass under a print head one time each in order for the ink to be deposited.

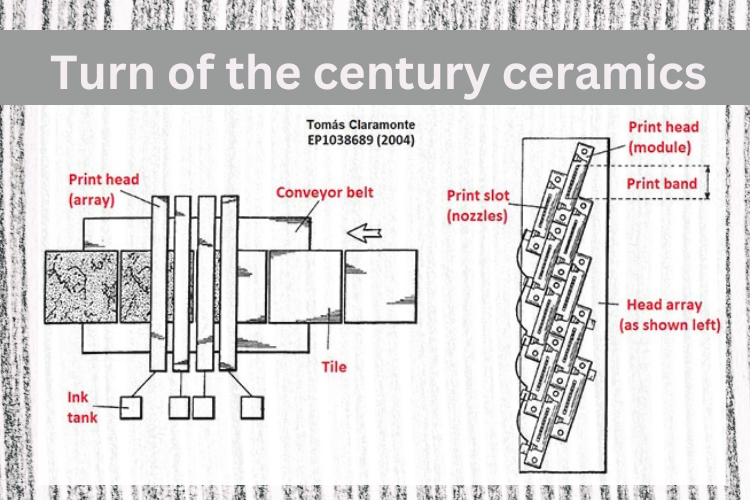

This is shown in the patent image from early machine innovators Kerajet, shown below, filed in 1999. The print head is rotated to make the head stitch, a process common with earlier print heads, including the Dimatix S-class range. Although this patent disclosed The Xaar XJ500, the Kerajet printer would adopt the Seiko 510 version of the Xaar technology.

The main difference between ceramic tile printing and many other inkjet applications is that the green tile “body” is not a solid surface. It is made from pressed powder and has been coated in a base glaze that has been dried, but it is still wet and often warm when it enters the printer. This means the materials are very specific to the market.

In their early patent on ceramic inks (US6402823), Ferro describes the printing of inks based on oils that are printed onto a glaze, also from Ferro. By combining digital and conventional materials, ceramics suppliers have created a solution for manufacturing, a bit like an optimized primer-ink combination in paper printing.

The Recirculation Revolution

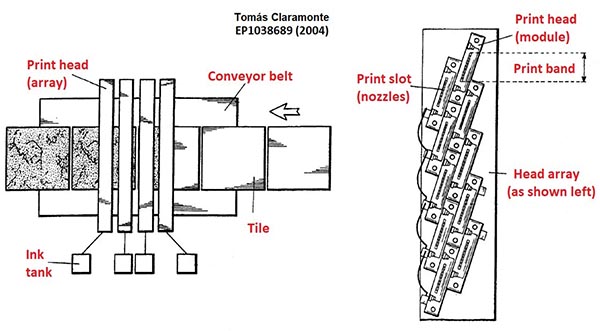

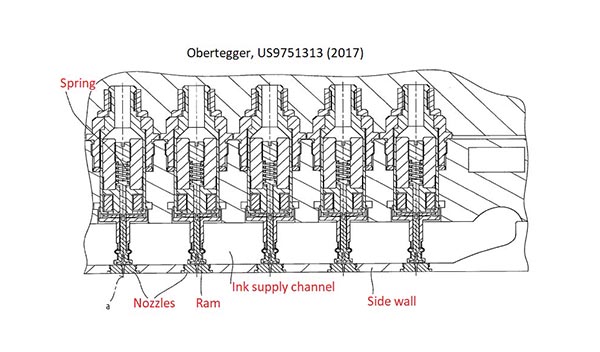

With the introduction of the Xaar XJ1001 in 2007, printer builders could improve the reliability of the system by using the ThroughFlow (TF) feature of the print head and achieve a 360DPI resolution. The patented TF Technology allowed the ink to be constantly agitated throughout the ink system, thus reducing the chance of pigment settling.

The design concept is captured above. The photo shows the finished head, whilst the patent image reveals the ink flow path when the silver nozzle guard and plastic nozzle plate is removed.

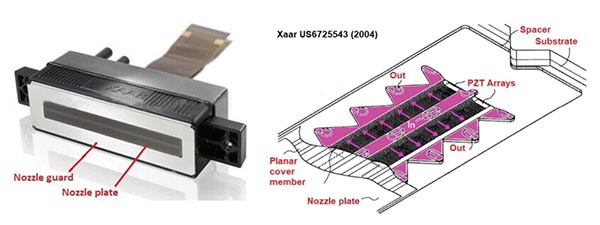

The images below demonstrate the differences seen when printing a tile with a Xaar head when different drop sizes are used. It shows how the smaller grayscale dots fill the space more evenly so that when viewed close-up they are not so easily visible. This reveals one of the reasons that tile printing was so successful early on—that some of the images can be a little more tolerant of defects than some other applications.

As time went on throughout the 2010s the head designs began to respond to the needs. Xaar produced a larger drop size head in 2012 in the form of the GS12. In the same year, Fujifilm Dimatix launched their competing 27pL SG1026MC “Starfire” heads. Seiko and Kyocera released their RC1536 and KJ-4C alternatives in 2015, and Konica Minolta followed up soon after with most offering the same 360dpi.

Which head to choose for any application comes down to finding the right DPI and frequency combination that matches the customer needs of print speed versus drop size and coverage and getting the widest fluid compatibility, including compatibility with water-based inks, for example. I covered this previously on an Inkjet Insight Inkjet Explainer Webinar with Mary Schilling on “Understanding printhead requirements for single pass applications.” Watch the replay here.

Ceramic Materials—Aqueous Inks and Beyond

The majority of conventional fluids used in ceramics lines are essentially water-based, and this led early innovators to experiment with aqueous inks way before the head technology was ready. In their early inkjet ink patent (US6402823), Ferro describes how it is useful to ensure the ink carriers were not miscible with water. They point out this reduces the migration of the ink when glazed. In that patent they also use soluble colorants to avoid settlement.

Quite quickly the market was driven by increasing cost competition toward solid pigments and lower cost carrier materials, the latter based largely on the price competition. Because the glazes contained water, additives were often required to prevent repulsion between the oil and water. It was therefore logical to look again at water as the carrier, which became a hot topic in 2013. This gave suppliers like Dimatix, a competitive advantage with their Starfire “SG1024..A” heads for Aq/UV/Solvent, complementing the “SG1024..C” for non-polar oil inks.

Whilst the traditional inkjet market drives to an ever smaller nozzle, ceramics have pushed the other way, demanding larger drop sizes driven by the desire to print effects. Tiles with mat, gloss and satin detail could be produced by adding extra heads into the printer layout. Such finishes allow for some convincing reproductions of wood grain, for example. This means the designer can mimic the look and feel of wood without the maintenance, especially when combined with underfloor heating. The challenges of such materials have again pushed print head development, with Dimatix now producing a higher flow (HF) variant of their Starfire head that is used in printers from System SpA.

Ceramics as Additive Manufacturing

Despite the piezo head advancements to provide 100-200pL at 360dpi, there is still a desire to increase the volume even further with the aim of achieving complete digital production line involving deposition of glazes to allow for structures prints. Therefore, the machine manufacturers turned initially toward valve-jet type designs that are quite common in large character coding and certain textiles applications.

In valve-jet, the ink is generally pressurized behind an actuated valve seal which opens to let some of the fluid out. Back in 2014, Sacmi and Colorrobia both show the capability at the Tecnargilla using the prototype Xaar 001 head. Since then, Durst has commercialized their RockJet, and other OEMs, like Kerajet, have also made their own solutions. Although generally lower in nozzle density, these large nozzle technologies more than make up for this with volume to achieve glaze coverages ~ kg per m2.

Suppliers are not making the printing line digital just for the sake of it. The new technology allows new designs to be taken one step further in terms of deposition. Of different materials with endless design options for combining topography, color and effects, including sticking powders or “grits” by the use of inkjet deposited glues. Production lines are becoming fully digital.

All About Design

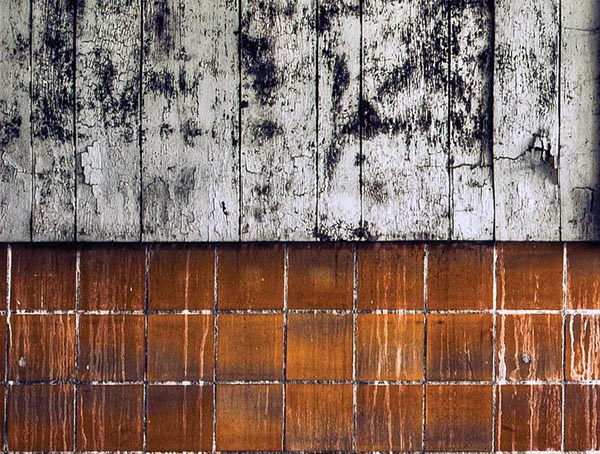

Older ceramic surfaces and chipped items can be re-created with near-infinite variation in texture and color to create interior designs

mimicking real dereliction.

Of course, the ceramic market has also adopted standard wide-format printer and inks (like UV-cured) in some niche applications. Mohawk tiles, for example, print a sandwich of ink and a primer/overcoat to decorate the edges of already-fired tile, whilst Italian finishing experts, Cefla, have decorating lines for ceramics using UV inks post firing.

Mimicking nature also requires a tactile appeal. 3D scanning of real surfaces has taken the décor industry to a new level of design. Re-creating such materials through print and image slicing has expanded the building and flooring industry’s decorative surfaces. Jetting various layers and patterns from the 3D slicing offer decorative layering, which builds into natural topical surface effects creating a realistic look and feel without infringing on nature itself.

Dr. Mark Bale is a published author of academic papers, patents, and online content on topics ranging from microfabrication, OELD devices, and inkjet printing. He isthe founder of DoDxAct Ltd, an inkjet technology consultancy. See all of his posts on Inkjet Insight.